Read the WSDA News Spring 2021 cover story to learn more about efforts to address workforce shortages, including new support for dental hygiene education at the University of Washington School of Dentistry.

QUICK BITES

- WSDA’s recent settlement with Delta Dental of Washington has paved the way for the two to address workforce shortages.

- The first example of this collaboration is important new support for dental hygiene education at the UW School of Dentistry.

- A creative review of dental hygiene education is needed to help increase the number of hygienists available to care for patients.

|

“Everyone talks about the weather,” the old joke goes, “but no one seems to be doing anything about it.”

Dentists in parts of Washington state can be forgiven for thinking the same thing about workforce shortages within the dental care community. These issues are well known, including having been the cover feature for the Winter 2019 issue of WSDA News and recently backed up by a variety of survey data. While many dentists are fortunate enough to be working in areas with an adequate supply of skilled staff, many others are feeling the pressures firsthand — especially in the hygienist ranks.

In addition to hygienists, shortages of qualified dental assistants are also being felt by dental offices across the state. Though current efforts by WSDA and other organizations — and much of the work discussed in this article — center on the dental hygiene shortage, the efforts are ongoing and will encompass the assistant shortage in the future.

REVIEWING THE DATA

In a joint effort to gather workforce data from multiple stakeholder groups, WSDA and the Washington Dental Hygienists’ Association (WDHA) developed surveys for dentists, dental hygienists, and dental assistants that were administered by the Washington State Department of Health (DOH) in fall 2020. The results, analyzed by Delta Dental of Washington and WSDA, found that the demand for dental hygienist positions in Washington significantly outweighs the supply of hygienists seeking positions.

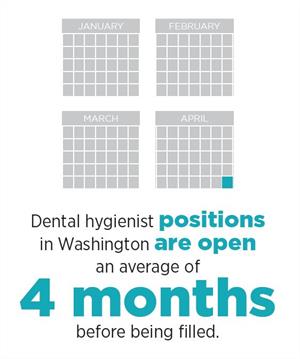

|

DOH Survey Highlights

- 926 total open dental hygienist positions were reported by dentists across the state.

- 221 hygienists reported currently seeking a position.

- Statewide, hygienist positions were open an average of 4.2 months before filled.

- While 52% of open positions were part-time, 29% of hygienists seeking a position preferred part-time.

- Counties with the greatest number of open positions were King and Snohomish.

- Counties with the greatest ratio of open positions to seekers were Thurston, Kittitas, and King.

|

Data also show that this serious workforce shortage has been made even worse by the COVID-19 pandemic. A recent study completed for the American Dental Association (ADA) and the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) found that 8 percent of dental hygienists have left the workforce during the pandemic, either because of exposure concerns or because of other issues like childcare responsibilities.

It’s unknown how many of these hygienists will return — or when they’ll be back. Some who were approaching retirement may choose to do so earlier than planned, rather than return. Whatever that percentage, it’s clear that the dental hygiene workforce is unlikely to return to pre-pandemic levels — which themselves were insufficient in some markets — until sometime after COVID is well under control.

WORKING TOGETHER

So, what can anybody do about the gap?

The first step is working together, according to Ryan Downing, president of Dental Connections, a dental staffing firm that has worked in western Washington for more than three decades.

“I think most dentists and hygienists feel like they’re on the same team in a clinical setting,” he said. “But when it comes to policy issues, it is unfortunate that they tend to treat each other like the opposition.”

“Hygienists don’t want an oversaturated job market making it hard to find employment or dramatically reducing their wages, and dentists deserve a good pool of job applicants so they don’t have to search for a new employee for many months at a time,” Downing continued. “I think both their needs can be met by adding hygiene school capacity in a responsible manner.”

ADDRESSING THE DENTAL WORKFORCE

A critical step in addressing the hygienist shortage is increasing the number of hygiene school graduates.

However, before adding new hygiene school capacity — either through creation of new schools or expansion of existing ones — it’s critically important to protect those schools that are already operating.

“First, we have to stop the bleeding,” said Bracken Killpack, WSDA executive director. “We can’t afford to lose any dental hygiene programs here in Washington.”

With that in mind, Killpack and WSDA’s volunteer leadership have been forging agreements on workforce strategy with another organization with which they’ve had more than their share of disagreements in the past.

Late last year, WSDA and Delta Dental of Washington reached a settlement regarding legal issues between the two organizations. According to Cindy Snyder, vice president of network strategy and business enablement at Delta, “We are thrilled to work together with WSDA on critical issues facing oral health in Washington, and one of the highest priorities is to expand access to high quality preventive dental care through growth of the dental workforce.”

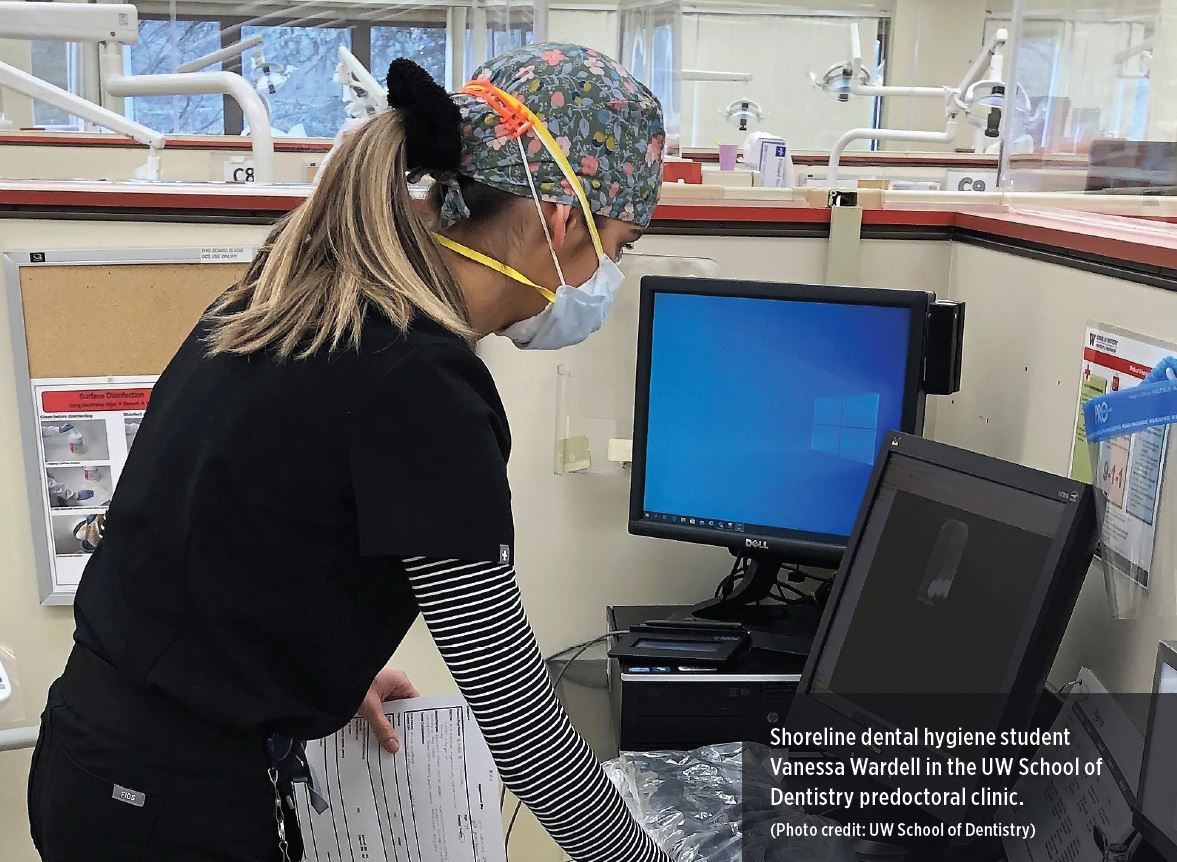

The first tangible sign of this shared commitment and collaboration was announced earlier this year, when Delta awarded a $1 million grant to the University of Washington School of Dentistry to support renovations needed after the dental school agreed to assume management of the well-regarded hygienist program previously operated at Shoreline Community College.

In addition to the initial $1 million grant, Delta has offered another $500,000 as a matching grant for monies raised within the dental community.

The WSDA Foundation committed to a $125,000 grant to jump-start dental fundraising, and the Seattle-King County Dental Society Foundation is considering a similar donation.

“The early commitment of these foundation dollars creates a manageable fundraising target for individual dentists and other organizations,” Killpack said. “By working together, we can ensure that UW School of Dentistry has $2 million for standing up the dental hygiene program formerly housed at Shoreline Community College.”

These dollars will enable the program to expand through larger class sizes, with a goal of enrolling 24 students annually within two years of expansion, and an additional focus on increasing the class size thereafter, Killpack added.

Shoreline dental hygiene student Vanessa Wardell in the UW School of Dentistry predoctoral clinic. (Photo credit: UW School of Dentistry)

FOSTERING NEW IDEAS

As significant as these grants are, Snyder believes another joint initiative may have an even greater impact in the long run.

Delta is partnering with WSDA, WDHA, and a group of education and workforce development experts on a “design sprint” to identify additional strategies for addressing workforce shortages.

It’s a process that has been used in a variety of organizational settings, but this collaboration is believed to be the first of its kind among a local Delta organization, state dental association, and state dental hygienist association, according to Diane Oakes, Delta Dental’s chief mission officer.

“When the dental delivery system doesn’t have enough team members to serve our patient population, that impairs access to care,” Oakes said. “So, we need to peel back the onion, understand root causes of why practices struggle to fill open positions, and identify solutions in a collaborative way.”

One key element of doing that through the design sprint is bringing together diverse perspectives. Participants will include representatives from different parts of the state, different care providers, different practice models, and a range of educational partners.

“The goal is to have everyone be able to see the problem through a different lens, one that might not be their own lens,” explained Cari Warren, who is customer insights manager at Delta Dental and a certified design thinking instructor. “We’ll spend time sharing perspectives, noting where more research is needed, and identifying who else should be interviewed to create a full picture of the problem.”

Several weeks later, the group will reconvene for a day of brainstorming. “At that point, we’re looking for quantity. Ideally, we’ll have hundreds of ideas. We want even crazy ideas, because they can evolve into something different and important,” she said. “Following the brainstorming process, a core group of representatives of the sponsoring organizations will hold a reflection session, where we’ll work with the education experts to narrow the focus down to a group of actionable items.”

“The design sprint is another example of our commitment to working with WSDA. First, in driving improved oral health care in the state, and second, to have good engagement and support dentists in Washington,” Snyder said.

CRITICAL CARE PROVIDERS

The focus on addressing hygiene workforce issues is a logical outcome of both those goals, according to Snyder. “Hygienists are critical providers of preventive care. When patients can’t get in for regular cleanings and other preventive care, it leads to more complex and costly treatments down the road.”

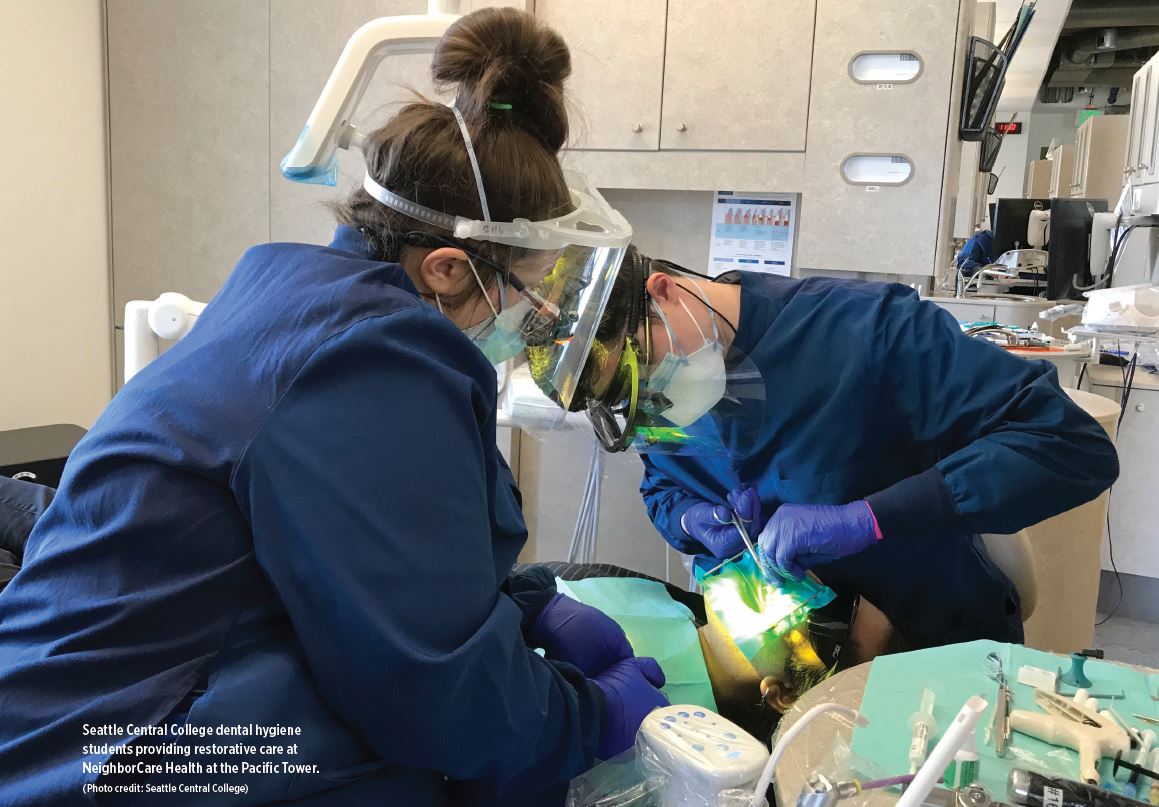

Brian Partido, executive director of the dental hygiene program at Seattle Central Community College, echoed the critical role hygienists play in providing care.

“Hygienists generally spend more time with the patient than the dentist,” he explained. “That’s where the relationships are formed, and that’s a great value the hygienist can bring to an office.”

Partido, who worked in the Bay Area and in Ohio before coming to Seattle, understands the direct link between the number of local hygiene preparation programs and workforce conditions in a market.

“In some markets in California, there are lots of programs and saturation of the market,” he said. “In Ohio, there’s great demand for dental hygienists, but not as many programs, so there are some shortages.”

Washington faces similarly divergent market conditions, with sufficient training programs to provide relative stability in the hygienist workforce in areas like Spokane, Yakima, and the Tri-Cities, but more serious shortages along the I-5 corridor.

Changing the number or size of hygiene education programs isn’t something that happens overnight, according to Partido.

“To start a new program, you have to demonstrate need to receive CODA accreditation,” he explained, referring to the Commission on Dental Accreditation. “And dental hygiene programs are among the most expensive programs for a college to launch, probably second only to nursing. The expert faculty and equipment are expensive to acquire.”

Cost challenges aside, the numbers at Seattle Central clearly demonstrate the need for additional capacity in the Puget Sound region. Partido’s program, which is located in conjunction with Neighborcare Health in the Pacific Tower on Seattle’s Beacon Hill, gets about three applicants for every one of the 20 spots that open each year, and every student has a job lined up before graduation.

Seattle Central College dental hygiene students providing restorative care a NeighborCare Health at the Pacific Tower. (Photo credit: Seattle Central College)

GETTING CREATIVE

According to former WSDA President Dr. Chris Delecki, who has spent his career in the public health sector, it will take both persistence and creativity to expand the supply of hygienists in Washington.

“Many of the dental hygiene programs have moved from associate to bachelor’s degrees,” Delecki said. “As education levels go up, so do salaries, but this shift has increased the time and cost for someone to get trained as a hygienist. That can be a barrier to low-income and diverse candidates from entering the hygiene ranks.”

“The system works well for those who can take four or more years out of their life and go to college full-time,” he continued. “But there are few provisions in our current educational system for individuals who must work and help support a family — something we see especially in diverse ethnic groups or individuals from families where English is a second language.”

The Seattle Central numbers bear him out. As a two-year program, it is more accessible to a more diverse range of students. In fact, two-thirds of those enrolled in the program are students of color.

“In a typical hygiene program, students must spend a full year fulfilling prerequisites before even starting their hygiene training,” Delecki added. “But there are private programs that build the prerequisites into a shorter, two-year curriculum. Maybe some of the public schools should look at what those private programs are doing to help redesign their programs.”

Delecki sees attracting a broader pool of students, including multi-lingual candidates, as important for the future of oral health care, where providers will be called to serve an increasingly diverse patient population.

“In dentistry, we rely on more real-time communication,” he explained. “In medicine, a doctor can often wait for an interpreter to care for a patient in an office or hospital setting. But in dentistry, the need to communicate often arises during the course of the procedure itself.”

This need to “come to the patients” is one reason he supports all stakeholders working together to create a better career ladder for the dental team.

“If you’re a dental assistant, the applied experience you have gained doesn’t shorten the amount of time it takes you to become a hygienist,” he said. “You basically have to go to school and start from square one. This can be a huge barrier for low-income and ESL students looking to move up the ladder.”

Delecki contrasted this disconnection between dental assisting and dental hygiene to the career ladder for nurses, where the various levels of nurses’ aides, LPNs, and RNs build upon each other.

Another step he thinks would help would be training and allowing assistants to do some hygiene tasks under close supervision of a dentist, such as performing simple cleanings. But that idea sparks opposition among the dental hygiene community, the sort of policy disagreement to which Dental Connections’ Downing referred.

One thing is clear: a growing patient population can’t afford to have good ideas pushed to the sidelines because of organizational conflict. That’s why the design sprint can be such an important tool in moving forward.

“WSDA will continue to update members and the dental community about the results of our various collaborations on workforce issues,” said Killpack. “The process is ongoing, and we’re excited to see the solutions that result from these efforts.”

As Delta’s Snyder said, “When we all — dental assistants, dental hygienists, dentists, and Delta — share a common goal and a common vision, we have a basis for working together, and we can advance farther and faster.”

SUPPORT THE SHORELINE DENTAL HYGIENE PROGRAM AT UW

To make a contribution to the Shoreline Dental Hygiene Program at UW Dentistry Fundraising Campaign, please visit

giving.uw.edu/dentalhygiene.

Your contribution will make a difference in educating and graduating more dental hygienists in our state!

This article was originally published in the Spring 2021 Issue of WSDA News.